I was always aware that I liked people. That I loved people. School was about cliques, but I bounced between them all. Everyone, anyone, was fascinating to me. Each person nuanced in their own way, with something special to share — and for some reason, they all shared with me. I had low-grade Williams syndrome, and I liked school, my art teacher, and girls. Every day, for six of my teenage years, I obsessively walked to school with one girl, while she slept with everyone but me. Despite being someone who was friends with everyone, I lacked confidence. So I took drugs. Stopped writing. Stopped walking to school with her. Stopped going to school. And found friends who really mattered to me. Three years later, when I realised I was adopted, my brain imploded — and while I sweated it out in rehab and dealt with paranoid psychosis, no one came to visit. The will to write and draw had been sucked out of me, and I couldn’t overcome a newfound shyness, an awkwardness, that continues to live with me today. So I picked up a camera and hid, discovering I could once again be near people, intimate with them, without having to engage. It was a new way to be social yet silent, to love and be distant. A barrier that gave me access to others, while I dealt with my own emotional trauma. It worked — and still works.

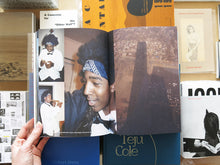

I met Josh and Mikey just off Canal Street, at a dim sum spot. It was February and freezing cold; they were visiting from California and weren’t dressed right, so we ate soup dumplings while Mikey stole sodas. Mikey loved Coca-Cola as much as Disneyland. It was the one day I didn’t have my camera. I was using a Pentax that year, and the winter was so cold it broke the winder and internal light meter. I was partially mute, making communication stilted. But Californians have an openness unlike anyone else, and that day conversation happened — or at least, I listened while they spoke — and a friendship, one that still exists, formed. I asked if I could join them back in California.

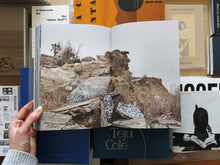

That summer, and for four more years, I traveled, tripped, couch-surfed, and found a family in Pan’s lost boys, wrestling with the end of youth, adulthood looming. When the sun shines daily, the days, seasons, and years merge, creating a temporal displacement that makes any narrative of truth near-impossible. But time and nostalgia also affect clarity: it’s taken me over twelve years to piece this story together. Now, my children are the same age as the characters in this publication, and I reside permanently in Los Angeles. My work is always about others, their lives and their experiences, but I don’t consider myself a documentarian. The camera is a tool and a vehicle: to engage, create, connect, contact. Something that’s now done by anyone with a smartphone and social feed.

Looking back, this was likely the last generation of teens who didn’t photograph their every waking move, but were at the gateway of tech communication. No one had a cell phone, but we all spoke on Myspace. 2005 was a very naive time … Nick Haymes

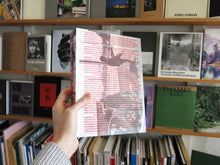

480 pages, 17× 24 cm, softcover, Kodoji Press (Baden).

I met Josh and Mikey just off Canal Street, at a dim sum spot. It was February and freezing cold; they were visiting from California and weren’t dressed right, so we ate soup dumplings while Mikey stole sodas. Mikey loved Coca-Cola as much as Disneyland. It was the one day I didn’t have my camera. I was using a Pentax that year, and the winter was so cold it broke the winder and internal light meter. I was partially mute, making communication stilted. But Californians have an openness unlike anyone else, and that day conversation happened — or at least, I listened while they spoke — and a friendship, one that still exists, formed. I asked if I could join them back in California.

That summer, and for four more years, I traveled, tripped, couch-surfed, and found a family in Pan’s lost boys, wrestling with the end of youth, adulthood looming. When the sun shines daily, the days, seasons, and years merge, creating a temporal displacement that makes any narrative of truth near-impossible. But time and nostalgia also affect clarity: it’s taken me over twelve years to piece this story together. Now, my children are the same age as the characters in this publication, and I reside permanently in Los Angeles. My work is always about others, their lives and their experiences, but I don’t consider myself a documentarian. The camera is a tool and a vehicle: to engage, create, connect, contact. Something that’s now done by anyone with a smartphone and social feed.

Looking back, this was likely the last generation of teens who didn’t photograph their every waking move, but were at the gateway of tech communication. No one had a cell phone, but we all spoke on Myspace. 2005 was a very naive time … Nick Haymes

480 pages, 17× 24 cm, softcover, Kodoji Press (Baden).