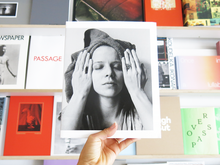

It was important to let my unconscious, rather than my intellect, dictate the progression. For reasons I don’t entirely understand, being nude became part of the project early on. And working against that white wall, near the two front windows in the so-called living room, became a central point. — Melissa Shook

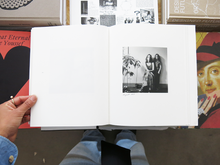

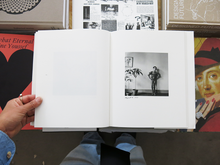

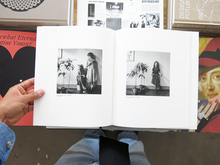

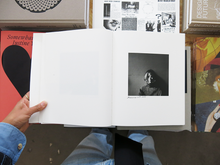

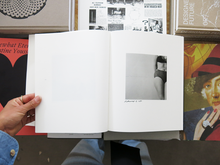

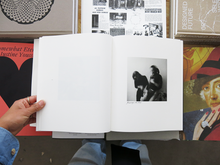

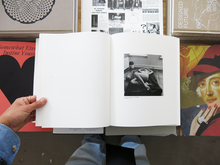

In December 1972, Melissa Shook (1939–2020) began a series of daily self-portraits in her Lower East Side apartment that she would continue until August 1973. Daily Self-Portraits 1972–1973 is the artist’s complete series of 192 photographs published together for the first time.

With her medium format, black and white photographs, Shook captures herself in a variety of poses creating a more complete portrait than could be achieved with any one image. The photographs often include Shook’s daughter and the friends who populate her sphere. The viewer is introduced to the artist’s intimate domain and the mundanity of everyday existence comes to the forefront: nursing her ailing toe on the couch, sitting at the kitchen table with a friend, hair wrapped up in a towel post shower, dancing with her daughter. Rather than strictly embodying a typical vision of beauty, Shook’s poses are often imbued with irreverence and parody as a rejection of the tradition of female portraiture made from a male perspective.

The book is astutely contextualised by Sally Stein's essay highlighting the artist’s purposeful dismissal of the idea of a single, revelatory moment, opting instead for the extended serial portrait, with all its contradictions and complexity.

400 pages, 20.3 x 25.4 cm, linen flexicover, TBW Books (Oakland).

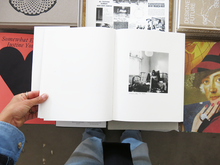

In December 1972, Melissa Shook (1939–2020) began a series of daily self-portraits in her Lower East Side apartment that she would continue until August 1973. Daily Self-Portraits 1972–1973 is the artist’s complete series of 192 photographs published together for the first time.

With her medium format, black and white photographs, Shook captures herself in a variety of poses creating a more complete portrait than could be achieved with any one image. The photographs often include Shook’s daughter and the friends who populate her sphere. The viewer is introduced to the artist’s intimate domain and the mundanity of everyday existence comes to the forefront: nursing her ailing toe on the couch, sitting at the kitchen table with a friend, hair wrapped up in a towel post shower, dancing with her daughter. Rather than strictly embodying a typical vision of beauty, Shook’s poses are often imbued with irreverence and parody as a rejection of the tradition of female portraiture made from a male perspective.

The book is astutely contextualised by Sally Stein's essay highlighting the artist’s purposeful dismissal of the idea of a single, revelatory moment, opting instead for the extended serial portrait, with all its contradictions and complexity.

400 pages, 20.3 x 25.4 cm, linen flexicover, TBW Books (Oakland).